The Mary Ann Forge has always been somewhat enigmatic for those who enjoy poking around the more obscure locations in the Pine Barrens. While many of you have read what Charles Boyer wrote about this location, for those who have not, I quote what he wrote about Mary Ann from his 1931 book, New Jersey Forges and Furnaces:

MARY ANN FORGE, Burlington County. It has been stated by several writers that this was furnace and was built in the early 1790s but there does not seem to be any foundation for either of these statements. It is not shown on any of the early maps examined nor is it mentioned in T.F. Gordon’s Gazetteer of New Jersey. The first map on which Mary Ann Forge appears is the Finley Map of 1831. The land on which this forge stood was long known as the Mary Ann Tract, on which there were several sawmills. On a map made in 1861, it is marked “Marian Forge.”

Benjamin Jones purchased this tract from John Black in May 1827, and a few years later built the Mary Ann Fore on Mount Misery Run about three miles southeast of New Lisbon. Its two hammers were supplied with pig iron from the Hanover Furnace. When Samuel H. Jones and Richard Jones purchased the holdings of their father, Benjamin, in 1846, this tract was included in the sale. Its subsequent history is closely interwoven with the many financial difficulties of the Jones brothers. In 1851, Samuel H. Jones gave a mortgage to Anthony S. Morris, trustee, for one-half of the Hanover Furnace Tract, Mount Misery Tract, Mary Ann Forge Tract, and several other tracts, which is the first recorded notice of the forge that has been located. The forge itself continued to be operated until late in the Civil War, and on a map made in 1877 is marked “not now in use,” and today the only trace of the old plant is a pile of forge cinders, the dam and sheeting.

The principal products of the forge were first bar iron. In later years, wagon axles and wagon tires were made on an extensive scale.

It appears Boyer conducted his research with due diligence, consulting both the deeds and the mortgages recorded in the Burlington County Clerk’s Office. Yet there are small errors in his account of Mary Ann. For example, the 1831 Finley map that Boyer cites fails to depict Mary Ann’s location and does not include a label for the place name:

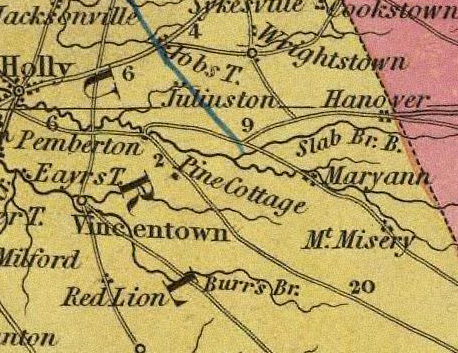

Even the 1834 edition of Finley’s map, included as the tipped-in, folded plate with Thomas F. Gordon’s A Gazetteer of the State of New Jersey… fails to identify Mary Ann Forge. It is actually the 1836 Tanner map that shows “Maryann” [sic] with three small black squares to indicate a small settlement or hamlet:

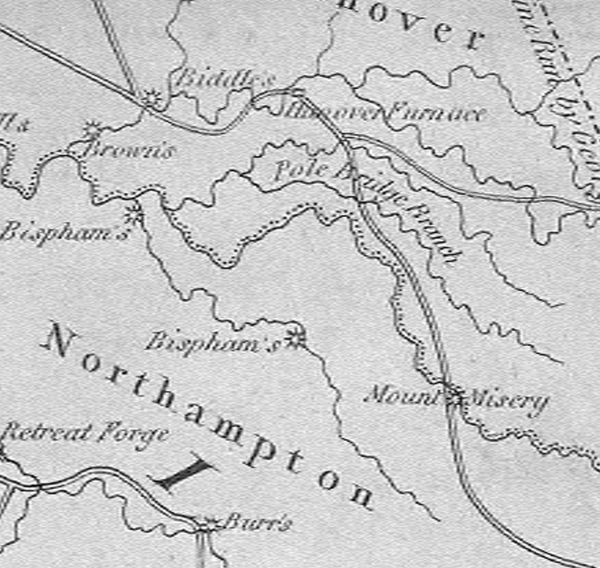

In checking earlier maps, like William Watson’s from 1812, there is no sign of any furnace or forge where Mary Ann stood later in the nineteenth century:

The first map that I have found that depicts Mary Ann is actually the revised edition of Thomas Gordon’s A Map of the State of New Jersey with Part of the Adjoining States, published in 1833. And based on the symbols employed on the Gordon map, this cartographer properly identified Mary Ann as a forge and not as a furnace:

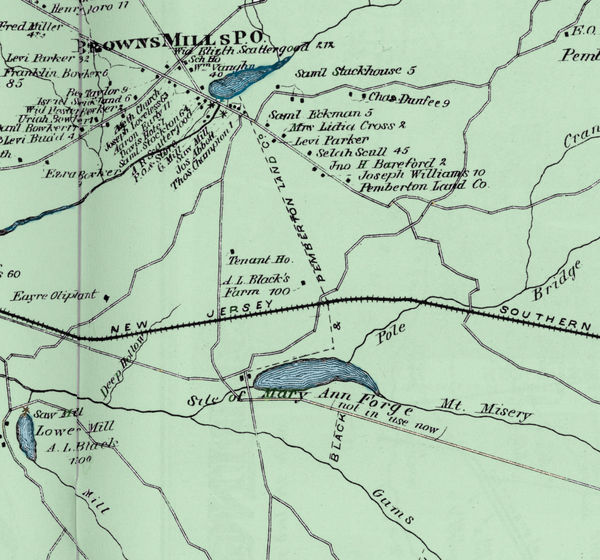

While Boyer properly notes that the Gordon Gazetteer did not include a separate listing for “Mary Ann” in its descriptions of localities, he did fail to record the presence of “two forges” within the description of Northampton Township, which at that time included present-day Pemberton Township. Ten years after Gordon published his gazetteer, John W. Barber and Henry Howe produced Historical Collections of the State of New Jersey and this work does enumerate “Mary Ann” among the localities within Northampton Township. The 1849 Map of Burlington County by A.W. Otley and E. Whiteford, provides us with the most detailed view of Mary Ann Forge and its small village of worker housing:

Note that Richard Jones maintained a residence at Mary Ann Forge, located near the forge’s furnace. The 1858 map of Burlington County by William Parry, George Sykes and F.W. Earl, has a rudimentary view of Mary Ann and lacks much of the detail the 1849 map provides:

Although the Jones family continued to operate Hanover Furnace until 1864, they also established a new ironworks at Florence, on the Delaware River during 1857-1858. Most sources indicate Mary Ann ceased processing Hanover iron sometime in the early 1860s. At some point, forging operations likely shifted to the Florence facility and Mary Ann became superfluous. The 1861 division of the vast Jones family land holdings left Richard Jones with the lower half of the property the “Marian Forge” and 25,145 acres. A member of these forums is a descendent of the Jones family and possesses an original edition of the published map that depicted the Jones’s expansive landholdings within the Pines.

Boyer mentions an 1877 map that shows Mary Ann Furnace as “not in use.” This is actually the Pemberton Township plate in the 1876 Scott atlas of Burlington County:

In Volume III of the Final Report of the State Geologist, C.C. Vermeule reported,

Mount Misery brook, at New Lisbon, will give for 9 months 5.6 horse-power per foot fall, and about 9 feet fall could be developed, or 15 feet by eliminating the power at Lower Mill. At the site of the old Mary Ann furnace there is 8 feet fall not at present in use. The water-shed is 38 square miles, and the available power 2.85 horse-power per foot fall. Just above this, at Mount Misery, a saw-mill was erected as early as 1723. Indeed, many of the sites on the Rancocas date back to about the beginning of the 18th century, and one as early as 1680. An important power was built at Pemberton in 1752 to operate a forge, saw and grist-mill.

At the Pemberton Railroad Station Museum, I purchased a booklet called Runaway by John C. Borton. The work provides “An account of a family log cabin on the upper reaches of the Rancocas Creek in New Lisbon, N.J. from 1916 to 1976.” While some of the information imparted concerning Mary Ann Forge is incorrect, it is still interesting to read an early twentieth-century account of visiting the abandoned site:

Mary Ann Furnace was a favorite trip. It was about 5 hours up stream from Runaway by canoe and three hours back. By foot it was about two hours each way. It was constructed in 1793 and produced iron from bog ore. An artificial lake provided power to work the furnace bellows and operate hammers to pound the molten iron to remove impurities. I have not found any record of how long the furnace operated, but it probably closed down in the 1840s when the iron ore and coal in Pennsylvania put the inefficient bog ore furnaces out of existence. When we first visited the site, all traces of the furnaces had disappeared, but most of the dam was still in place. A few lumps of slag were the only evidence of the once prosperous furnace. Near by was delightful pine grove where we had many happy picnics. Swimming in the stream above the broken dam was always refreshing.

The booklet includes several photographs of the ruins at Mary Ann when these explorers visited the site during the 1920s and 1930s.

At some point in time following the cessation of ironworking, the area around Mary Ann Forge became dedicated to cranberry production.